Many dyslexic and dyspraxic child struggle to learn how to tell the time. This can lead to frustration and embarrassment, but also a poor sense of time.

Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â

Why do some learners find it difficult to tell the time?

Time is not a solid measurement … an hour in the dentist is very different to an hour enjoying yourself.

Â

When a child is surrounded by absolute measures such as litre, metre and month, it is easy to see how they might expect an hour to be more solid and predictable than it actually is. Talk about this with your child to make sure they know how variable time can appear to be.

Also, the analogue clock face can be very confusing with its directional and linguistic codes (‘clockwise’, ‘half past’, ‘quarter to’ etc) … I do believe these early confusions can befuddle a brain and switch it off to both clocks and the development of other time-related skills.

Â

Teaching the telling of time

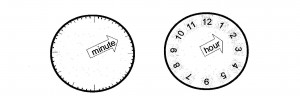

A teaching method I have found works very well is to separate a clock face into two: one is a minutes’ clock-face marked with dashes and the other is an hour clock-face marked with numbers.

Establish the clockwise movement by relating it to something already in long-term memory:

If they do not know the ‘on = clockwise’ and ‘off = anticlockwise’ movement, then practise with a real tap until they do.

Another question they often ask is Which hand is which?

I show them the two words ‘minute’ and ‘hour’ and the two hands and ask them to match the length of each word with the length of the clock hand (i.e. the minute hand is longest so has the longest word).

(You also need to talk about the second hand once the lessons here have been learnt.)

Display different times by using the two clock faces for the learner to read.

Ask them to quiz you too.

BUT to avoid confusion, do not use terms such as ‘quarter past’ etc and ’20 minutes to’ … keep the time-phrase as always saying ‘X minutes past the Y hour’ such as:

20 minutes past 4 o’clock

35 minutes past 5 o’clock

55 minutes past 10 o’clock

The minutes are counted in dashes starting at the top and moving in a clockwise direction. The minute hand pays no attention to the numbers around the clock face (only the hour hand does that).

Once they see that the bigger dashes are units of 5, they can use that to aid their counting.

By using two clock faces, the separation between minutes and hours is much easier to see. And any confusions they might have by thinking the minute hand is related to the numbers around a clock’s face, is removed.

By using ONE WAY of telling the time (a number of minutes past the hour), clocks can be used to build up confidence and accuracy. Later on, the learner can use terms such as ‘quarter past’ or ‘twenty to’; once they understand what they mean.

When they can tell the time using the two clock faces, put the clock-face together and practise using it.

Expect it to take two or three separate lessons for the learning to become established … each lesson reminds and recalls past memories, building up confidence and success.

Using digital clocks

Most people see more digital clocks than analogue ones.

Moving between digital and analogue displays is made so much easier if you use the ‘X minutes past the Y hour’ mode outlined above.

Digital clocks use the same language, but just in a different order so …

40 minutes past 8 o’clock = 08:40

Making sense of the 24 hour clock

To explain the 24 hour clock, I draw a wavy line across a page and label the peaks 12 midnight and the troughs 12 noon.

I then place marks to denote hourly divisions along the line.

We then go through a storyline, filling in the hours as we go:

|

12 midnight |

It’s midnight and most people are asleep in bed; it is dark outside; is that an owl I hear hooting? |

|

1 o’clock |

One hour later and it’s now one o’clock in the morning (fill in the number one as you talk). Granny is snoring and the newborn baby next door wakes up for a feed. |

|

2 o’clock |

One hour later and it’s now two o’clock in the morning. The nurse in the hospital is checking the patients are asleep and a cat is quietly checking for mice in the farmer’s barn. |

|

3 o’clock |

At three o’clock in the morning, the Hart family are leaving for Cornwall. They have a six hour drive and want to travel while the roads are quiet. Granny is still snoring. |

|

And so, as the morning ticks away, make up your own story together to match time with related events. |

|

|

Once you get to 12 noon, continue the story into the afternoon: |

|

|

1 o’clock |

An hour later and it’s one o’clock in the afternoon. The sun is shining and the baby is sleeping outside in its pram. |

|

2 o’clock |

At two o’clock in the afternoon, the children at school are doing history. They learn that the Romans used sun dials to help them track time during the day and candle clocks at night. |

|

When you reach midnight, the day is over. |

|

|

Now go back to 12 noon and explain how the 24 hour clock is used to save us from saying whether a time is in the morning or the afternoon. In other words, the hours are numbered 1 to 12, and then, instead of starting at 1 again, the numbers continue on to 13, 14, 15 etc up to 24. |

|

Having a pictorial representation of the hours throughout the day, makes it easier to explain how the 24 hour clock is used.

Use time to play games, quiz each other and make use of the clock.

The more confident a learner becomes with the topic, the better they get at using time to help them.

Please let us know if you find this teaching advice helpful.

All comments and queries welcomed at sally@dragonflyteaching.org